OUT OF ORDER

Capturing “Cool” – An Homage to an Homage

Watch below and scroll down to read about the process and inspiration!

TECHNICAL SPECS: 35mm Kodak film stock (5203, 5207, 5213, 5219). Aspect ratio: 1.66. Lenses: Kinoptik 28mm, 35mm, and 100mm. Laboratory: Fotokem.

BACKGROUND: While Flash Frame was a more spontaneous and experimental work, guided by images rather than a storyline, I went into Out of Order with a direct plan: to make a film that satirized and paid homage to the French New Wave crime films I admire so much – specifically Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Cercle Rouge and Le Samourai; and Claude Lelouch’s La Bonne Anne and Le Voyou.

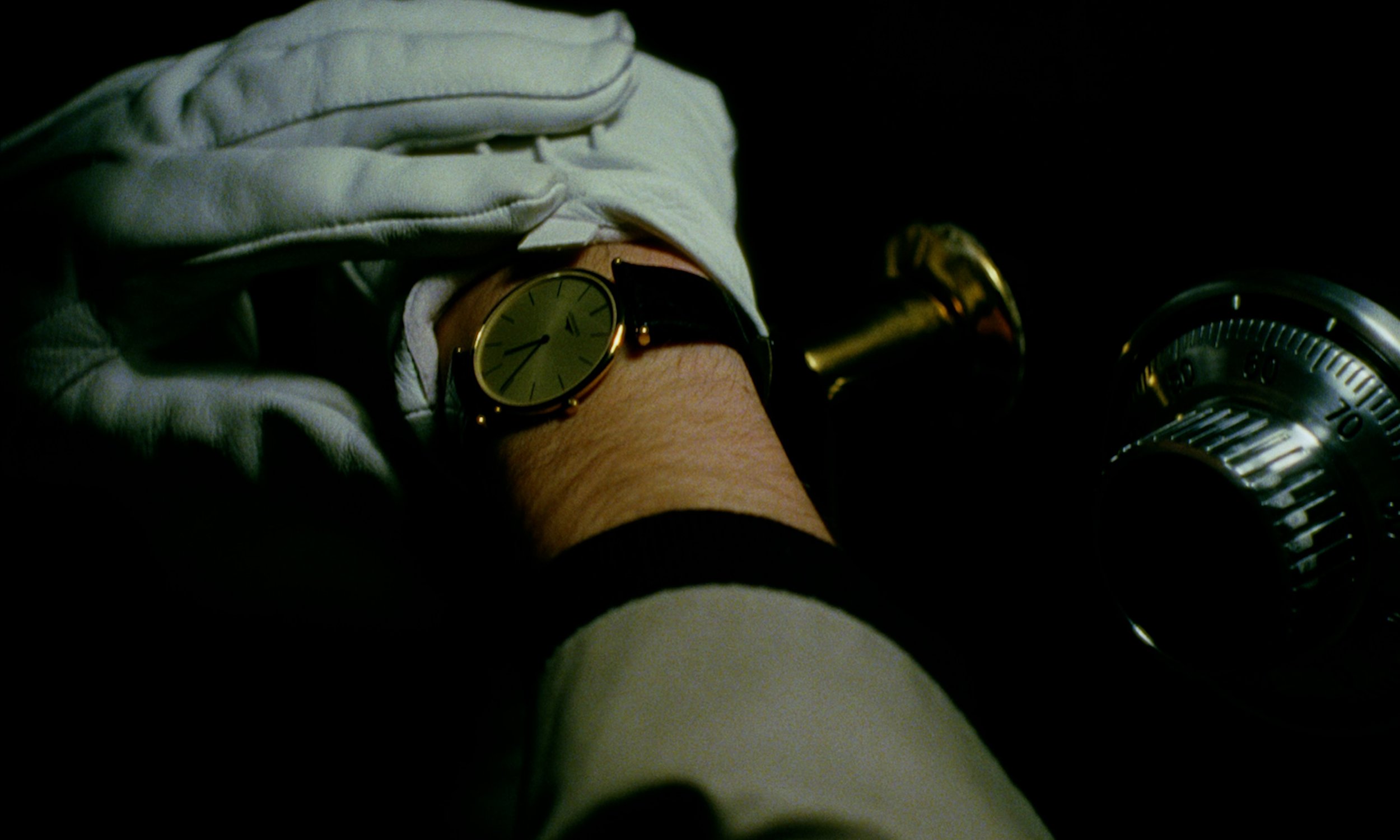

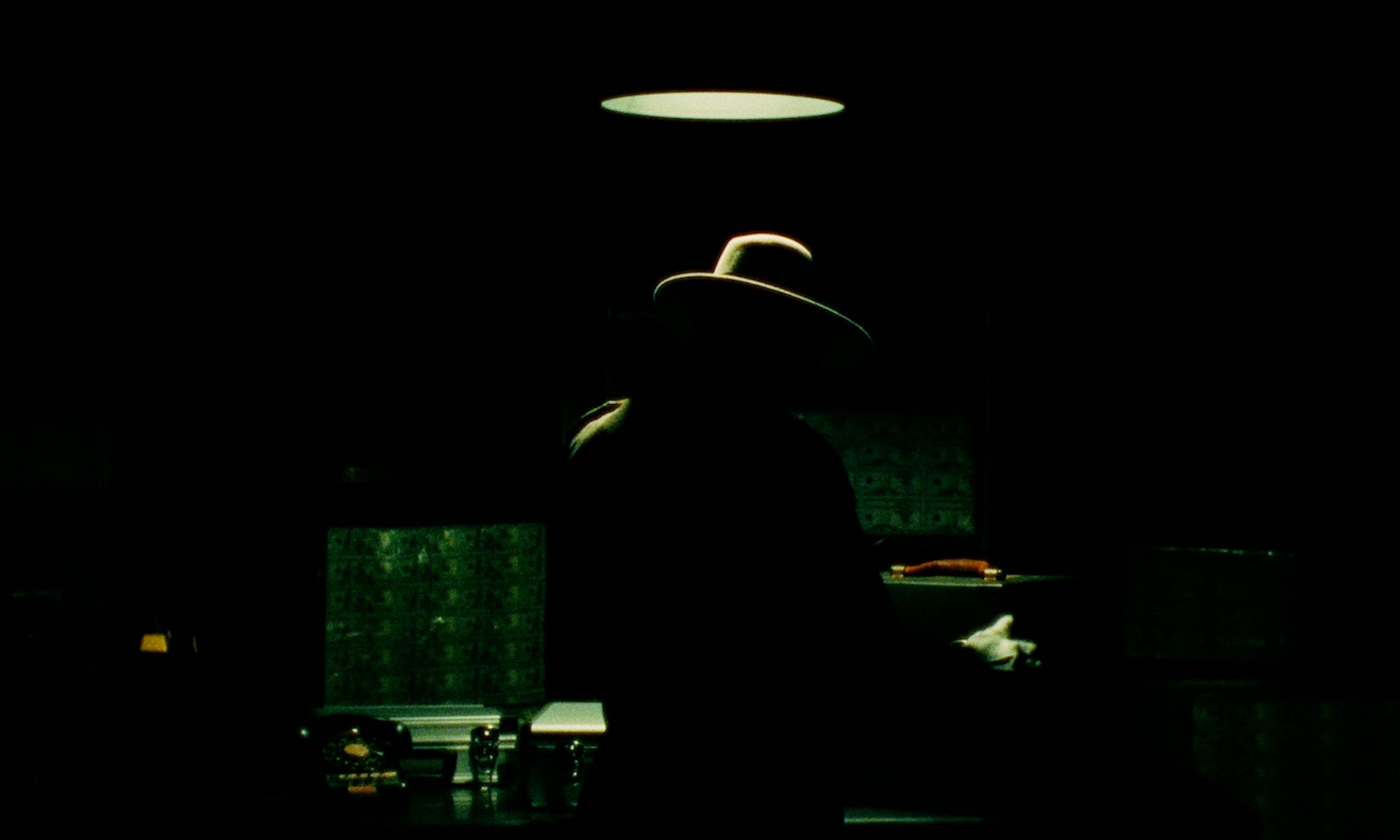

What fascinates me – and I think most fans of these films – is the effortless “cool” factor. They exist in a fictional universe that seems equal parts familiar and strange. Many of them, Melville in particular, were influenced by 1940s American film noir movies. Le Cercle Rouge and Le Samourai are marked by the appearance of a mysterious protagonist in a uniform of a trench coat, white gloves, and hat, silently moving about a city, his every action made cinematic by dramatic lighting or captivating mise-en-scène. The protagonist says very little, but expresses a lot. He is routinized, efficient, and stylish. Each action is deliberate and intentional, but not obvious about its intentionality. Gangsters like this only exist in films – but despite the ridiculousness of it all, it is engaging enough to convince the audience to play along. The look of these films is beautiful, and Melville mentioned wanting to make a film noir in color, which gives them a rather striking look: dramatic, but still understated.

WHY: When starting this project, my question was: what is this extraordinary, fascinating, rare Alain Delon, Jean-Louis Trintignant, or Yves Montand-type like when he’s not “on”? Or is he always “on”? How would he fare in the rather mundane requirements of everyday life? Is he indeed a compelling person, or just adept at finding great lighting to commit crimes? Having never been a stylish gangster myself, I worked backwards from the tropes to see what might be there.

GETTING THE LOOK: I decided to lean more into the camp factor when it came to the acting, but maintain a grounded approach to the visual aesthetic. Emulating the look was simpler than it could have been because I again used the Eclair Cameflex and its Eclair-mount Kinoptik lenses, which was very popular for New Wave filmmakers during that era (though I don’t know what lenses specifically were used for these films, or how much of them were filmed on the Cameflex. They appear to have used it at least partially, according to behind-the-scenes photographs.) I used practical or natural lighting whenever possible, and four 35mm film stocks, shooting without any filters. With the talented finishing editor Stephen Boyer, we brought out as much as we could from the rich film stock while preserving the natural look and feel of it, leaning more towards blues and greens for interiors, muted colors for exteriors, and crushed blacks to capture the noir aesthetic. For the aspect ratio, I went with 1.66. Although Le Samourai and Le Cercle Rouge were in 1.85, 1.66 was also a popular aspect ratio in Europe at the time, and I believe it emphasizes the physical comedy a bit better.

CAPTURING SOUND: Capturing the sound was another interesting task. Many of these films have long stretches of silence, or simple sequences with music, which are mostly visually-based with a few ambient sounds thrown in. For me, this sound design emerged as a practicality to deal with the Cameflex’s notoriously loud noise while running; it’s incredibly difficult to shoot dialogue unless you have a long lens or a hundred-pound blimp. It was shot MOS and we dubbed the dialogue and added all sound effects in post, which was tricky, but not as difficult as I’d imagined. We added subtitles to avoid the problem of dubbing dialogue that was not meant to be heard. This was my first time ever trying to dub dialogue, and I was surprised by how realistic it sounded.

Even if these reference films had adequate shooting conditions for sound, they effectively harnessed the power of the understated soundscape. When most of the film is quiet, you pay more attention to the sounds that are there, and you have room to think about what you’re shown. A loud camera forces the filmmaker to be more creative with visual storytelling and more intentional in their use of sound. It’s not the quantity, but the quality of sound, that matters.

FINAL NOTES: I like a creative challenge, and this project certainly presented a great deal of new situations to address. At the end of the day, what I wanted to make was a fun and engaging piece that captures the spirit of these films. I hope you enjoy it as much as we enjoyed making it.

Official Selection: Chattanooga Film Festival, San Antonio Film Festival, ASCF Film Festival, We Make Movies International Film Festival. Semi-Finalist: Richmond International Film Festival.

With Claude Lelouch!

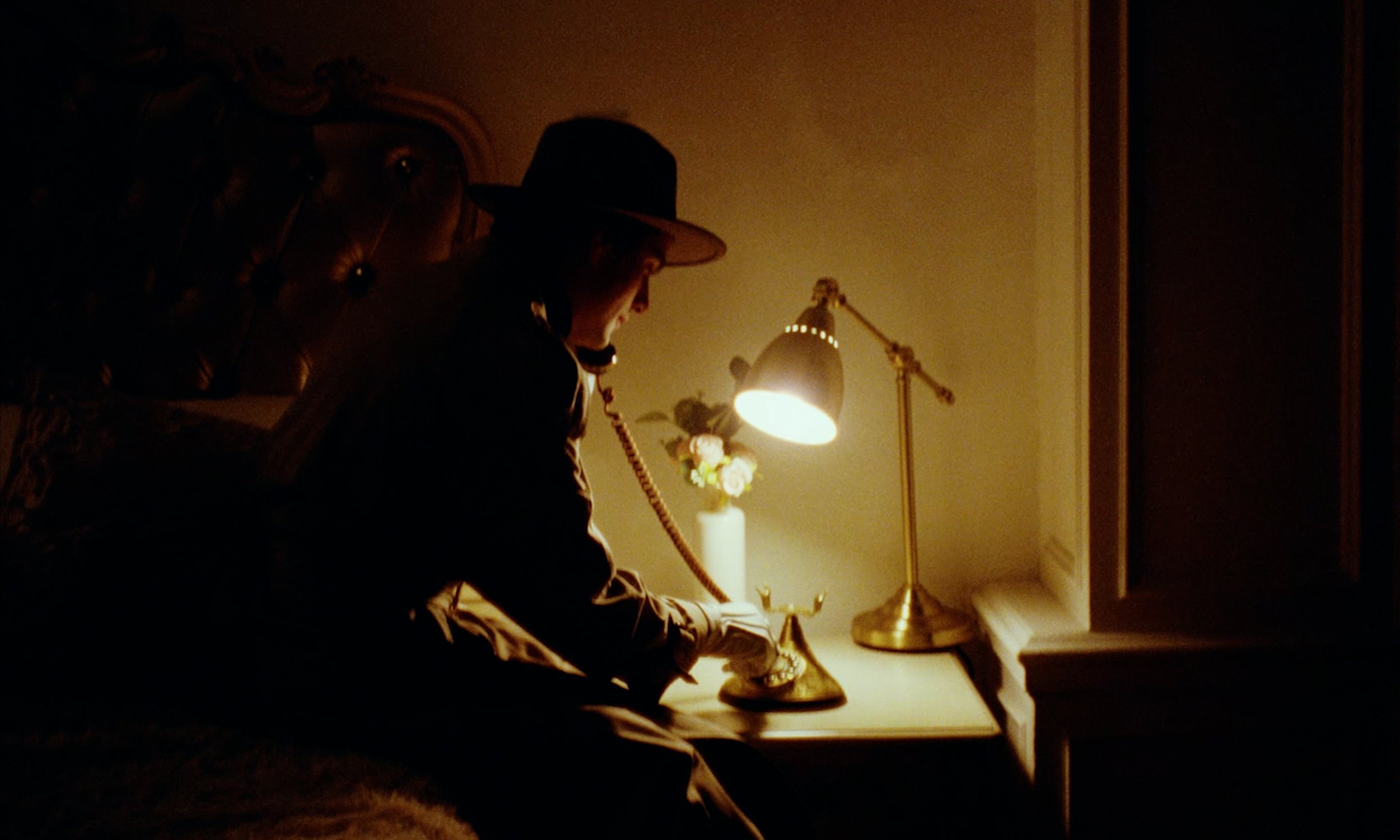

Some stills from reference films (top) with their inspired counterparts from Out of Order (bottom)

Le Samourai

Out of Order

Le Cercle Rouge

Out of Order

Le Samourai

Out of Order

Le Samourai

Out of Order

Le Samourai

Out of Order

Le Samourai

Out of Order